Whenever we try to define American food, we often find ourselves in a complex and ever-shifting landscape. It’s a question that goes far beyond simple recipes or restaurant reviews, delving into the heart of cultural identity and historical evolution. This complexity was vividly illustrated decades ago, as highlighted by a note sent to the Los Angeles Times Food Section back in March 14, 1991. An irate reader, feeling the publication had strayed from “American” culinary traditions, expressed her displeasure in no uncertain terms.

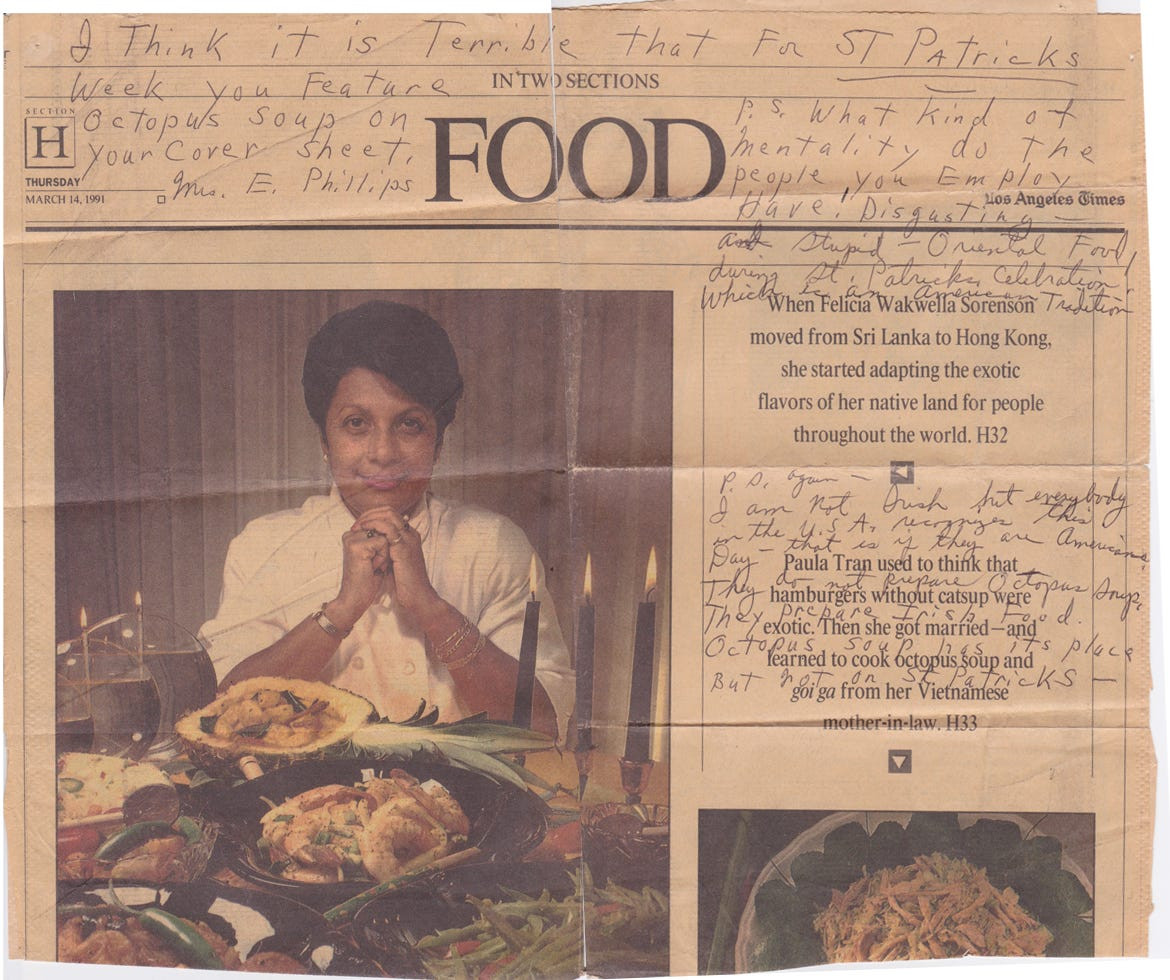

Vintage Los Angeles Times Food section cover from March 14, 1991, showcasing a reader's handwritten angry note criticizing the newspaper for publishing "Oriental food" recipes during St. Patrick's Day, highlighting a historical perspective on defining American cuisine.

Vintage Los Angeles Times Food section cover from March 14, 1991, showcasing a reader's handwritten angry note criticizing the newspaper for publishing "Oriental food" recipes during St. Patrick's Day, highlighting a historical perspective on defining American cuisine.

The reader’s outrage stemmed from the Food Section featuring articles about two accomplished cooks, one Sri Lankan and the other learning Vietnamese cuisine from her mother-in-law. For her, this was an affront, especially during St. Patrick’s Day, which she deemed an “American tradition” demanding “Irish food.” Her stark declaration, “Octopus soup has its place, but not on St. Patrick’s day,” underscored a rigid, and ultimately limited, view of what constitutes American cuisine.

This incident, though from the past, resonates deeply today. The debate over what truly defines American food continues, albeit in more nuanced and evolved forms. While in 1991, patriotism might have been linked to cooking corned beef and cabbage on St. Patrick’s Day, today, the conversation has shifted to encompass questions of cultural ownership, authenticity, and the very right to engage with certain culinary traditions.

American food has always been a dynamic entity, constantly shaped by the waves of immigrants who have arrived on its shores. Each new group brought with them unique flavors, cooking techniques, and culinary perspectives, enriching the existing tapestry of American gastronomy. What was once considered foreign gradually becomes integrated, adapted, and eventually, Americanized.

The seemingly simple question, “What Is American Food?” unravels layers of complex issues. Not long ago, a non-native chef cooking Mexican or Chinese food might have been lauded for their culinary exploration and appreciation. Today, the same act can be viewed through the lens of cultural appropriation, raising crucial questions about authenticity, respect, and the line between homage and theft. Our understanding of these dynamics is continually evolving.

Consider the now widely accepted and celebrated category of hyphenated-American cuisines: Chinese-American, Italian-American, Mexican-American, and many more. Dishes like orange chicken, spaghetti and meatballs, and hard-shell tacos, once dismissed as bastardized versions of classic cuisines, have not only gained immense popularity but are also being reimagined and elevated by chefs across the country. These dishes are now undeniably part of the American food narrative. But who has the authority to claim these recipes? Is it necessary to be a third-generation hyphenate-American to truly own them? The communities that introduced these flavors and techniques certainly deserve recognition, yet at what point do these culinary ideas become so ingrained in the mainstream that they enter the public domain, becoming universally accessible and “American”?

The political nature of food becomes even clearer when we consider events like the Latinx food issue published by Gourmet magazine in 2007. Intended as a celebration of Central and South American culinary traditions, it was met with unexpected backlash, with readers accusing the magazine of injecting politics into their food content. Despite the absence of overt political statements, the very act of highlighting Latinx cuisine was perceived as a political act, highlighting the inherent connection between food and identity.

Indeed, asking “What is American food?” is far more profound than simply inquiring about dinner. It is a question about identity, belonging, and the ever-evolving cultural landscape of a nation built on immigration. It’s a question that forces us to confront our history, our values, and our relationship with the world around us.

Even a seemingly straightforward dish like octopus soup, as mentioned in the reader’s letter, opens up broader conversations. Today, we wouldn’t just consider its place on a St. Patrick’s Day menu, but also its provenance. Where was the octopus sourced? Were sustainable fishing practices employed? Were the fishermen fairly compensated? And in an increasingly environmentally conscious world, we might even question the ethics of consuming such intelligent creatures at all.

Looking back at that decades-old letter, it becomes evident that food, and all the questions surrounding it, encapsulates the complexities of our world. It reflects our history, our values, our anxieties, and our aspirations. It’s a lens through which we can examine who we are as individuals and as a nation.

Reflecting on the ever-expanding definition of American food also brings to mind the evolution of dining experiences. Menus from the past offer a fascinating glimpse into the culinary trends and social customs of different eras. Consider, for instance, a menu from a star-studded dinner in 1987, a time when fine dining in America was reaching new heights of sophistication.

This menu, featuring classic French-inspired dishes like “Consommé aux pointes d’asperges” and “Mignonettes de boeuf aux morilles,” alongside a curated wine list and elegant dessert options like “Charlotte aux framboises,” represents a specific moment in American culinary history. It showcases a dedication to refined techniques, imported ingredients, and a formal dining experience that was once considered the pinnacle of American gastronomy.

However, American food is not confined to such high-end experiences. It is equally present in the everyday ingredients and pantry staples that reflect our diverse culinary landscape. Consider the Alphonso mango, often hailed as the king of mangoes, a fruit not native to America but now readily available in various forms, symbolizing the globalization of American palates.

Products like Alphonso mango puree, easily accessible from brands like Pure Indian Foods, exemplify how global ingredients are becoming seamlessly integrated into the American kitchen. This puree, perfect for lassi, sauces, or even a simple spread on toast, represents the evolving American pantry – one that embraces flavors from around the world and constantly redefines what “American food” truly means.

In conclusion, “What is American food?” is not a question with a simple, static answer. It is a continuously evolving concept, shaped by immigration, cultural exchange, historical context, and contemporary concerns. American food is a vibrant, dynamic, and inclusive cuisine, constantly borrowing, adapting, and innovating. It is a reflection of the American people – diverse, complex, and perpetually in search of their own identity.